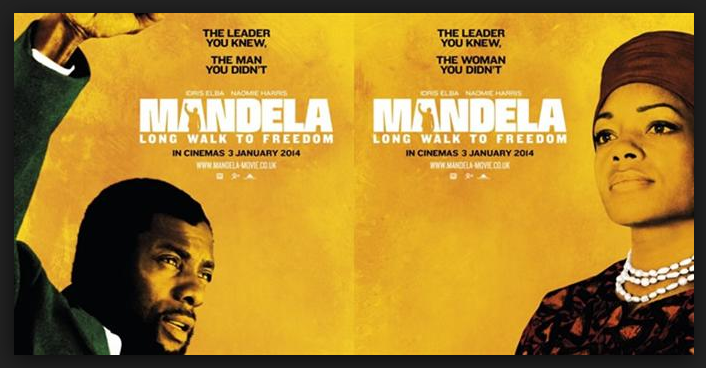

Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom dynamically portrays Nelson Mandela’s and the country of South Afrika’s struggle to achieve liberation from the oppressive European (Afrikaner) regime from the 1940s to the end of apartheid in 1994. Directed by Justin Chadwick, the film aims to tell an often-untold story about Mandela and the experiences he, his wife Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, and the entire Black South Afrikan people endured in order to attain true democratic rule. Mandela features two stellar performances by Idris Elba, as Nelson Mandela, and Naomie Harris as Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

The apartheid system in South Afrika was extremely oppressive. By 1899, the British and the Dutch had both settled in the country, yet both had competing interests: the British were interested in exploiting South Afrika for its natural resources while the Dutch were mainly motivated by religious reasons to settle within the country to preserve their language and culture. Consequently, a major conflict ensued. The Boer War (1899-1902) was extremely bloody. The British lost over 70,000 troops and the Dutch (or the Boers/Afrikaners) lost around 4,000 troops. Nevertheless, an armistice was formed which allowed for the Afrikaners to keep their weapons and the preservation of their language and culture while the British would exercise effective control over South Afrika’s mineral wealth under the advisement and accord of the Afrikaners. By 1910, The Act of Union was established between the Dutch and British without the consent of the Black majority, which made South Afrika an independent nation-state initially controlled by British politicians. Eventually, the Afrikaners eased the British out and were able to establish an increasingly oppressive apartheid regime.

Immediately after the Act of Union came to effect, the Black majority created the Native National Congress (NNC), which was founded in 1912. The NNC transformed into the Afrikan National Congress (ANC), which Nelson Mandela became a leader of in the 1940s. Mandela was a skilled lawyer, as portrayed in the film. Through legal channels, the ANC aimed to secure legal rights for all Black South Afrikans, yet they were largely ignored. Whites systematically eliminated Blacks in governmental roles. By 1959, Blacks lost the ability to gain strong footing in the political system. Thus, the systems of apartheid further intensified while other Afrikan countries were winning their independence from their colonial oppressors.

Working as a lawyer, Mandela aimed to advocate for and organize with the Black majority to fight for basic human rights, yet the apartheid system was so oppressive, he ultimately changed his approach after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960. After a day of demonstrations, a crowd of about 5,000 to 7,000 Black protestors went to the Sharpeville police station. The South Afrikan police opened fire on the crowd, killing 69 people. The film does an outstanding job in portraying the brutality and devastation of that tragic day by inserting real-life images of the massacre within the scene. As a symbol of resistance, as the film also portrays, Mandela helped organize Black South Afrikans to burn their citizenship passes, which they were legally obliged to carry. In the film, Mandela boldly states while burning his pass, “I can not support a government that wages war on its own people.”

The massacre moved him so much that even though he was initially committed to non-violent protest, he co-founded the militant Umkhonto we Sizwe (abbreviated as MK, translated as “Spear of the Nation”) and in 1961, he lead a bombing campaign against government targets. In a thrilling and climatic scene, Mandela attempts to run from a safe house that the police were raiding, however, he was soon caught. Consequently, in 1962 he and his accomplices were arrested, convicted of sabotage and conspiracy to overthrow the government, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

At this time, he was married to 21-year-old Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, South Afrika’s first Black professional social welfare worker. They were married for three years and they had two daughters, Zenani (3 years of age) and Zindzi (two years of age). Shortly after his conviction and during his imprisonment, Winnie was arrested by the South Afrikan government and served 18 months in solitary confinement for an unwarranted charge. After she was released, Winnie came out angrier and more determined to fight against the unjust and oppressive apartheid regime. She began to lead an international advocacy campaign calling for Mandela’s release. Ultimately, through various negotiations with then President F.W. de Klerk, and through added pressure from the international community, Nelson Mandela was finally released in 1990. Mandela served 27 years in prison.

The expression of Black love, and more specifically the relationship between Nelson and Winnie, and the way in which it was affected by the apartheid regime, was especially riveting to experience on screen. After Mandela’s release, the two became very distant. In one scene, Mandela suggests that he and Winnie stay in separate houses for the “sake of the party” (ANC) given that she advocated for Black South Afrikans to riot, whereas Mandela was starting to take on a more non-violet approach. Winnie expressed that she was tired of being alone. To this, Mandela coldly asserted that she was not the only person who has been alone for too long. This scene exquisitely and subtly exposes how once seemingly undying love can be completely dispirited and even destroyed by oppressive systems like the apartheid regime.

In one of my favorite scenes, Chadwick juxtaposes the images of riots in the South African shantytowns or Bantustans with Bob Marley’s ‘War’, a song that is infamous for lyrics that originated from a speech made by Ethiopian Emperor, Haile Selassie I, before the United Nations General Assembly in June 1936:

That until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned; That until there are no longer first-class and second-class citizens of any nation; That until the color of a man’s skin is of no more significance than the color of his eyes; That until the basic human rights are equally guaranteed to all without regard to race; there is War…. And until that day, the Afrikan continent will not know peace, We Afrikans will fight – we find it necessary. And we know we shall win, as we are confident in the victory of good over evil, yeah!

I thought I knew Nelson Mandela’s story. Throughout my childhood, I saw Nelson Mandela as a symbol of peace and diplomacy. Through my involvement in the Afrikan Student Union, I learned about Black student activists who helped lead a divestment campaign against UCLA for investing in The Coca Cola Company and Bank of America, corporations that had economic ties to the apartheid regime. In my third year, I took an Afrikan Politics course with Professor Edmond Keller, where we learned about Mandela and the South Afrikan region. Yet, I did not fully grasp the totality and the richness of his narrative until watching this film; Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom beautifully portrays the often un-told story about this revolutionary freedom fighter. Ironically, I recently noticed an illustration of Nelson Mandela accompanied with a quote, which currently hangs on a wall in the Afrikan Student Union Office: “Only through hardship, sacrifice, and militant action can freedom be won. The struggle is my life. I will continue fighting for freedom until the end of my days.” Madiba forever.

* Madiba means father in Xhosa, the tribe to which Mandela belongs. He is often described as “The father of the nation”.

Mandela opens in select theaters November 29th

Author: Kamilah Moore/ ASU Chair

Nommo Contributor